Frank Stewart has seen it all. Growing up in the segregated South, he began taking pictures at the age of 13 during the historic March on Washington in 1963. Since then, this Tennessee-born creative has made a career – and a life – portraying world cultures and Black life in America through music, art, travel, and dance.

On October 14, Frank Stewart’s Nexus: An American Photographer’s Journey, 1960s to the Present will debut at the Baker Museum in Naples. Co-organized by The Phillips Collection and Telfair Museums, this is also the first major museum exhibition of Stewart’s work. Tracing both Stewart’s explorations of life on the road and his journey as a photographer, the exhibition brings together a comprehensive list of over 100 black-and-white and color photographs as well as a selection of materials from his personal archives.

As the senior staff photographer for Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra for 30 years, Stewart captured both public performances and candid moments from jazz legends such as Miles Davis, Ahmad Jamal, Wynton Marsalis, and several others. Additionally, Nexus provides a window into less-explored aspects of Stewart’s practice, including his Drawings series, which is inspired by the artist’s travels.

Ahead of his opening in October, Stewart spoke with ESSENCE about his new exhibition, photography, creative inspirations, and more.

ESSENCE: The name of the exhibition, Nexus – how did you come across that name and what inspired you to name it that?

Frank Stewart: Well, Nexus encompasses a lot and it’s like the vortex of all things. So that’s kind of how I came across Nexus. It’s cultural. Well, my career has always been culturally-motivated. And it spans a bunch of African American cultures because we don’t have just one culture, you know? Different regions have their own culture in terms of African American. I grew up in three different regions of African American culture.

What regions were those?

Well, I’m from Tennessee. I was born in Nashville, grew up in Memphis, and then moved to Chicago and then moved to New York.

You’ve taken so many photos within your career. How did you decide what photos to put in this collection?

We had about three or 400 images, and Ruth [Fine] was the one who narrowed it down. And I either approved or disapproved of what she had – then we had to narrow it down to the hundred that’s in the book. So it was an interesting process.

Do you have a specific or favorite place to shoot? A specific city or region or area that you like to shoot that you get the most from?

Well, they are all kind of special. I love New Orleans, you know. Back in the day, I was there two, three times a year every year. But recently, I love Savannah, Georgia a great deal, too. It reminded me so much of Memphis and how I grew up. So I’ve taken a lot of pictures in Savannah. And New York, of course. I’ve taken a lot of pictures in New York. And I’ve taken a lot of pictures in Chicago too. So those three cities are my favorite backdrop.

Those places are all musical cities, and music is the focus of a lot of your photos. Jazz, in particular. What was it about jazz music that intrigues you?

Well, the thing is, jazz is the only art form that came out of America. I mean, recently hip-hop, but jazz was the only art form to come out of this country. Growing up, you were never taught that you had a culture, that you had a history. I grew up in the segregated South. So I was always wondering where this came from, how did this music come to be?

So, I went to Africa to find out where those polyrhythms came from and how it got started, and saw the drum and what importance the drum had in the society of West Africa where the slaves came from. Then I went to Cuba after that to see how it got codified once it got to the new world in the Caribbean, and found out that New Orleans was not a part of America, it was the northernmost city in the Caribbean. So all these things went into the basic codification of what became jazz in the 19th century. Then it went to Chicago and New York and it became something else.

That’s why jazz was the basis for everything. it was like the groove of the culture for me; that’s why I chose jazz. My stepfather was a jazz musician – Phineas Newborn Jr. So I got a real dose of jazz early in my life.

How was it being the staff photographer for the Lincoln Center for three decades?

Well, that came about because I did a book on Wynton Marsalis called, Sweet Swing Blues on the Road, which was about his septet as they traveled. That took about two and a half years to finish – from start to finish – ending in 1989. That just morphed into me taking pictures of the orchestra, the jazz orchestra when it first got started. They got started with the septet and the surviving members of Duke Ellington’s orchestra.

So that was how that got started. And then they just hired me to take pictures. At first I wasn’t taking pictures. I was like a road manager driving the truck and helping get from one place to the next and getting people on stage. But I was still taking pictures of Wynton and the septet to do this book, and it just transitioned into me taking pictures of the orchestra, The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

So being an artist, what inspires you to take your photographs? What is it about it that makes you want to do it and you make it your life’s work?

Well, from an early age, I liked taking pictures. I think the first pictures I have is when I was about 13 or 14 at the March on Washington.

I had an aunt that had a boyfriend that was a photographer. And she was always bragging about him, and I asked her one time, “Well, what does he do?” She said: “He’s a photographer. You could never do that because you have to have brains to do that. You got no chemistry,” and this, that, and the other. So I always thought that that was something unattainable until I started actually doing it. She should see me now.

So I always liked the medium and what the medium did and how it changed what I saw. So, that’s been the impetus for taking pictures. Robert Sinstack was my first teacher, and he lived in the same complex that I did. I used to work for The Defender back in the day, and from there I went on to being a stringer for Ebony. I just liked doing it. I liked the whole process. I liked working with the cameras. I like sweeping the film. I like developing the prints. It was a whole lifestyle. It’s still a lifestyle. I’m still doing the same mess that I started out doing in my teens.

When people visit your exhibition next month, when they leave, what message do you want them to take from it?

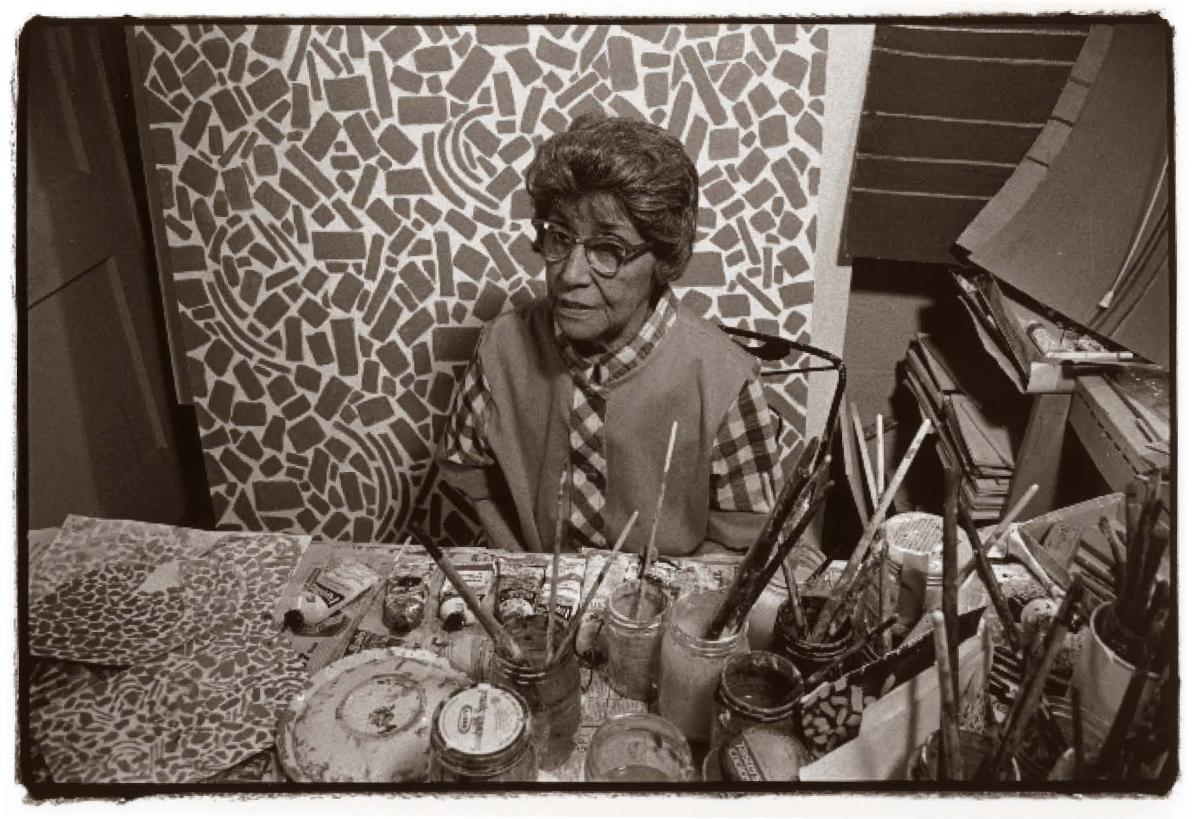

Oh, that’s a good question. I want them to see that I’m not just a jazz photographer either. I’m an artist and I’m not just a photographer. I’m an artist. I want them to see the art that you can make with this medium and not just documenting a situation. I want them to see that you can actually make art with this camera.